The Wandle has seen dramatic change over the last 150 years. In this article, local historian John Hawks looks back at Merton’s transformation – from peaceful countryside to industrial sprawl, and finally to urban renewal. He reflects on what was lost, what was saved, and how the river endures.

John Hawks fell in love with Merton in 1989 when he became founding manager of Merton Abbey Mills. He is Vice Chair of Merton Priory Trust and Wandle Heritage Limited, a Trustee of the Wandle Industrial Museum, a member of the Wandle Valley Forum, and Curator of the Chapter House Museum.

THINGS AREN’T WHAT THEY USED TO BE – THANK GOODNESS!

Being so near London the Wandle has seen more than its fair share of changes. On its way from the North Downs down to the Thames our precious chalk stream – said to be one of only around two hundred in the world – once passed through rural villages and unspoilt countryside. In less than 150 years the villages have become commuter towns and inner suburbs, with all the infrastructural problems they bring.

But still the Wandle takes its peaceful course through some beautiful parks, and is still a priceless green corridor – a perfect example of what the ancient Roman writer Martial called “rus in urbe” (the country in the town).

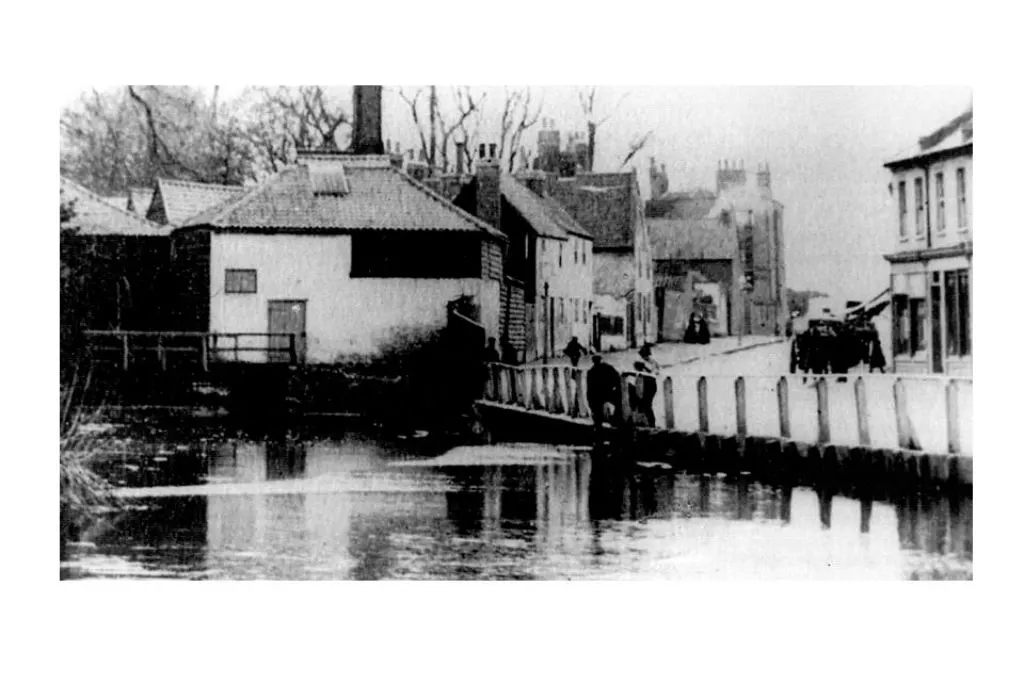

One of the biggest changes of all has been in Merton – once a remote country village, now a busy London borough. And nowhere have the changes been more marked than in Merton High Street. For two millennia it’s always been a main road, of course, the ford where the Roman Stane Street crossed the Wandle.

There were watermills on the river and charcoal burners in the nearby woods (where the name Colliers Wood comes from), but the predominant scene would have been meadows and fields with scattered dwellings.

In 1117 the canons of Merton chose to build the great Priory there by the river, (naturally enough, for a fresh water supply) and on the Roman road (not just beside it but in the very middle of it!), for ready access for of all their many visitors – indeed, a monastery was, among other things, a harbour for travellers. But around this great building it was still pure countryside.

Much later, when Nelson left Merton Place for Trafalgar in 1805, the village scene hadn’t changed much, and in 1880 when William Morris found his ideal premises there, an old Huguenot fabric works on the Wandle, the great surge in Victorian suburban building had only just begun, and the High Street was still pleasantly rural.

Alas, I wonder how many of you will be old enough to share my own vivid dystopian memory of Merton High Street 90 years later, which couldn’t be more different. For a month in 1969 I had to drive every day from Mitcham through Colliers Wood, along the High Street and down Haydon’s Road to Wandsworth.

West of Christchurch Road was a ghastly dump of abandoned railway sidings, car breakers, plant hire, rubbish exchange, skip companies and low grade industry in the final throes of dereliction as far as the eye could see. The Wandle was grossly polluted – it had recently been designated “a sewer” – the Pickle a filthy overgrown ditch, and even the precious relic of the Priory wall hidden and jostled by factory buildings.

The only landmark in Colliers Wood was the infamous black tower block, built in 1967, and once voted “London’s ugliest building”.

And the High Street itself was utterly dominated by the hideous Merton Board Mill, which gave the entire area the appearance of the worst kind of Northern industrial town.

Oh, and by the way this narrow confine was still the main A24 to Dorking, inevitably a horrendous traffic bottleneck into the bargain – it felt like being trapped in Hell.

No single person or policy had done this to poor little Merton – it had just happened incrementally as the years went on, industries flourished and died, an accident of history, the whole area in a kind of slow death spiral. And yet this was SW19, for goodness sake, a postcode shared with affluent leafy Wimbledon, just a mile away!

The longed for solution came in the mid-1980s, and the White Knight, perhaps unexpectedly, was Sainsbury’s. In just five years the entire industrial area was swept away, a new bypass built, the Liberty works relaunched as Merton Abbey Mills, the historic Priory site excavated, the Wandle revived and landscaped, and the High Street once more neat and tidy – if, admittedly, a little bland.

Yes, the quid pro quo was a giant hypermarket, and the era of “shed retail” had come -but the nightmare was over, and Merton and its precious river could be lively and lovely again. Even the hated black tower now has a new set of clothes, and is really rather nice.

And the brave little Wandle, as ever, is the life blood of the place, patiently coping, suffering, surviving, nourishing, calm, placid, reassuring, ever constant while all around it is constantly changing.

Douglas Pollard

Friday 28th of March 2025

A lovely backdrop to all the work of Wandle News. It should inspire us all to contribute. Thank you, John

Peter Evans

Saturday 22nd of March 2025

Nice article John Hawks