Brunel’s Tunnel, also known as the Thames Tunnel, was the first tunnel to be built under the river Thames. It was also the first underwater tunnel to be built anywhere in the world. This post is all about Brunel’s Tunnel, including how you can visit it today.

Brunel’s Tunnel runs from Rotherhithe to Wapping. Between 1845 and the early 1860s it was used as a pedestrian foot tunnel under the Thames. In 1865 the tunnel was bought by the East London Railway and turned into a railway tunnel. Today the tunnel is used by the London Overground.

Brunel’s Tunnel

Why was the Thames Tunnel Built?

In Victorian times, the river Thames in Rotherhithe was a busy area of docks. There were thousands of merchant ships and small boats coming down the Thames bringing trade to London, but also creating traffic jams on the water.

The closest bridge to Rotherhithe was London Bridge, which was over two miles away, and was very expensive to use. Merchants complained that the cost of transporting goods across the Thames by bridge or boat, cost them almost as much as if they’d brought the goods from America.

The area urgently needed another crossing, but one that would not interfere with the docks, or ships travelling down the Thames. In 1825, Marc Isambard Brunel, a French-American engineer set out to build the first tunnel under the Thames. The project took eighteen years, and was finally finished in 1843.

Who Was Marc Isambard Brunel?

Marc Isambard Brunel was a civil engineer. He is most famous for constructing the Thames Tunnel, and for being the father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, one of Britain’s most iconic engineers.

Brunel was born in France in 1769, and fled to the United States during the French Revolution. He became the Chief Engineer of New York City in 1796, before moving to London in 1799.

The same year he moved to London he married Sophia Kingdom who he had met in France over ten years earlier. The couple had two daughters, Sophia and Emma, and a son, Isambard.

Isambard ended up becoming a great engineer, who was more famous than his father. He worked for the first three years on the Thames Tunnel project until 1828 when the tunnel collapsed and Isambard was almost killed. After this he never returned to the tunnel again.

Marc Brunel’s daughter Sophia was also interested in engineering, and had been described as “Brunel in petticoats”. She was a talented women who understood her father’s plans and regularly visited the tunnel. Unfortunately in Victorian times women we barred from any form of higher education, otherwise Sophia may also have been a great engineer.

The Building of the Tunnel

The building of the Thames Tunnel was one of the most exciting engineering projects in the world. Other people had attempted in the past and failed, due to the difficultly of tunnelling through soft soil.

A previous attempt was made by English engineer Richard Trevithick, who managed to build the first tunnel to pass underneath water. His attempt was abandoned in 1808 however, as he was unable to build through the quicksand under the river.

Two decades later, the American French engineer Marc Brunel came up with a way to tunnel through soft soil. He was inspired by a type of worm called a Teredo Navalis. The worm would eat through the timbers of ships and excrete the wood out of its body to line a tunnel behind it as it moved.

Marc Brunel used the same technique as the worm. As men dug the tunnel, a “tunnelling shield” moved along the tunnel with them. The tunnelling shield was a complex set of boards, screws, jacks and runners that supported the soft earth, and prevented collapse.

Although the tunnelling shield helped to get the tunnel built, it was far from perfect. The miners still had to work through layers of clay, quicksand, river mud and gravel, which meant progress was slow. The tunnel also flooded five times between 1825 and 1843.

The Design of the Tunnel

Brunel’s tunnel was designed to have two separate passages, that would be linked by small archways, so that you could pass between the two.

One tunnel was designed to transport goods via horse-drawn carriages, and the other was for foot traffic. The tunnel ended up only being a pedestrian walkway however, as no facilities for horse-drawn traffic were ever added.

The picture below shows what the tunnels looked like when they first opened. The entrance was via an octagonal building, with staircases leading down, and the walls and floor were decorated with white and blue marble.

The next picture was taken at Wapping overground station where you can see what the tunnels look like today. The staircase leading out of Wapping station is the same staircase that was built by Brunel’s workers.

The Opening of the Tunnel

Brunel’s Tunnel was finished in 1843. Instead of being a practical route across the river, it became a vibrant tourist attraction with 50,000 visitors on its opening day. After 15 weeks, 1 million people had visited, which was half of London’s population at the time.

People travelled from all over the world to see the tunnel, including experts from foreign governments, who wanted to learn from this triumph of British engineering. The tunnel even had an unexpected visit from Queen Victoria, who turned up to see it three months after it opened.

The tunnel was celebrated all across Europe, with guidebooks being printed in many different languages. People began calling it the “eighth wonder of the world”.

Timeline of Brunel’s Tunnel

Brunel’s Tunnel was meant to take 3 years, but ended up taking 18 years to complete. The timeline below shows the progress on the tunnel from when work started in 1825, to when it was first opened to the public in 1843. It also shows the timeline of what happened to the tunnel after it opened.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1825 | Work on the Thames Tunnel began. |

| 1826 | Marc Brunel’s son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, was appointed as Chief Engineer at the age of 20. |

| 1827 | The tunnel was flooded. After the tunnel was drained and repaired, a banquet was held inside it. |

| 1828 | The tunnel flooded again, this time killing six workers and almost killing Isambard. The tunnel was bricked up for several years after this, whilst money was raised to complete it. Isambard resigned and never worked on the tunnel again. Whilst recovering from his injuries he began designing the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol. |

| 1828-1835 | Work on the tunnel was abandoned for seven years due to financial problems. |

| 1835 | Construction on the tunnel started again after Marc Brunel had raised £247,000. |

| 1841-1842 | The tunnel was fitted out with lighting, roadways and spiral staircases. |

| 1843 | The Thames Tunnel was opened to the public. In its first 15 weeks, one million people visited. |

| 1852 | The tunnel became a spectacular underwater fairground with sword swallowers, fire eaters, magicians and tightrope walkers. One section of the tunnel was turned into a ballroom where a steam powered musical organ played dance tunes. |

| 1865 | The tunnel was purchased by the East London Railway company. |

| 1869 | The tunnel was converted into a railway tunnel and used by the East London Line. |

| 2010 | The tunnel began to be used by the London Overground under the ownership of Transport for London. |

What Happened to Brunel’s Thames Tunnel?

When the tunnel first opened it was a popular tourist attraction, but by the 1850s visitor numbers had started to decline.

The tunnel became a dangerous place, that was notorious for pick pockets and thieves. Since it was open all night, it was also used by the homeless, who could pay a penny to enter and stay until the morning.

The tunnel was eventually sold to a railway company in the 1860s, and has been used as a railway tunnel ever since.

How to Visit Brunel’s Tunnel Today

Brunel’s Tunnel is still in use today by the London Overground. If you travel to Wapping station, you will be able to see one of the original entrances. I took the below photograph from the platform of Wapping station where you can still see the original marble entranceway, with the two passages.

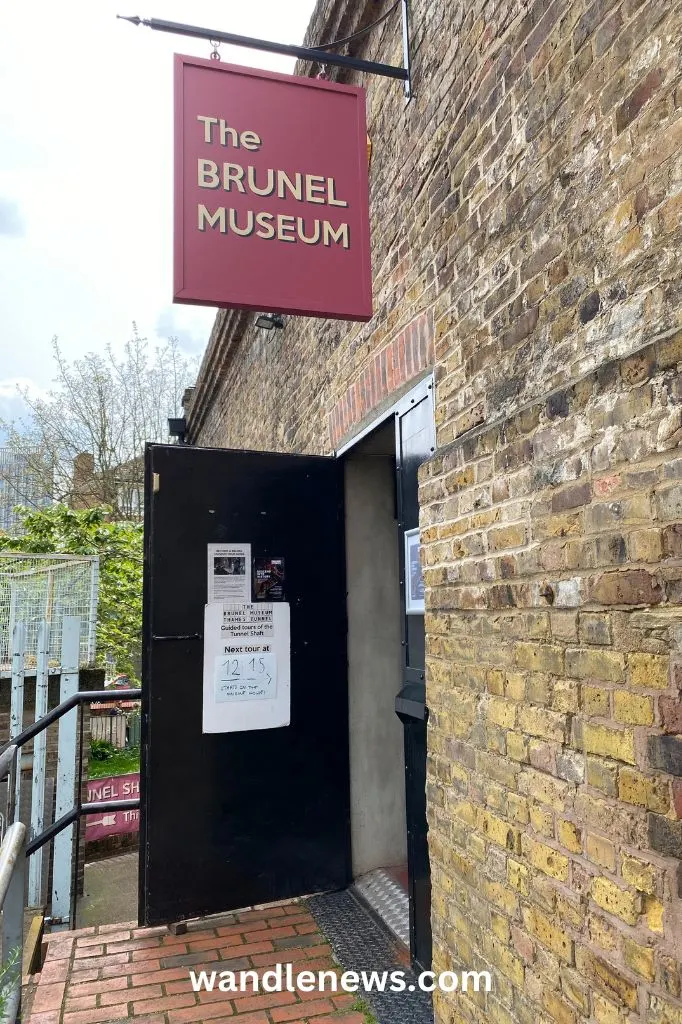

If you visit the Brunel Museum, which is located at the Rotherhithe entrance to the tunnel, you can walk down the vertical shaft that once led to the Grand Entrance Hall. This is where work on the tunnel first began, and where Marc Brunel created the ‘sinking’ shaft to dig deep into the ground.

Today, the shaft has been converted into a performance space, where music and theatre events are held. You can still see the marks from where the original staircase stood, as well as black soot on the walls from the Victorian steam trains.

Photographs of the Brunel Museum

Below are some of the photographs I took when I visited the Brunel Museum. If you want to visit the Brunel Museum, the nearest station is Rotherhithe on the London Overground. When I went I attended a guided tour. The tours take place over four weekends a year.

Roof Garden at the Brunel Museum

The top of the shaft that once led down to the Thames Tunnel, has now been turned into a candle-lit roof garden by the Brunel Museum. It’s a great place to go for summer cocktails around a fire pit, and all proceeds go towards the upkeep of the museum. The photograph below shows the roof garden in the daytime.

Other Attractions in Rotherhithe

If you are visiting the Brunel Museum, below are some other attractions that you may want to visit nearby.

This Post was About Brunel’s Tunnel

Thank you for reading my post about Brunel’s Tunnel. The Thames Tunnel was one of the most exciting engineering projects in the world. Until the space race, no other feat of engineering had attracted so much attention. When it first opened it was a major tourist attraction for London, but today is used by the general public for train journeys.

Peter Evans

Tuesday 17th of December 2024

Another really interesting article Olivia. Useful dates for the tunnel tours.